cross-posted from: https://sh.itjust.works/post/55510704

Daniel “Des” Sanchez Estrada is set to be tried starting Tuesday on charges of corruptly concealing a document or record and conspiracy to conceal documents. He’s been in custody since July and in federal prison since October (save for a brief accidental release before Thanksgiving, during which he spoke to The Intercept). He and his codefendants were recently transferred to county jail to await trial. Supporters report that they’ve been placed in solitary confinement and are dealing with other horrid conditions.

In plain language, Sanchez Estrada is facing up to 20 years behind bars for allegedly moving a box of anarchist zines from his parents’ house to another residence in his hometown of Dallas. His indictment came on the heels of Trump’s signing an executive order to classify “Antifa” as a “domestic terrorist organization” and issuing National Security Presidential Memorandum 7 (NSPM-7) on Countering Domestic Terrorism and Organized Political Violence.

Sanchez Estrada’s case originated with a July 4, 2025 anti-ICE protest his wife, Maricela Rueda, attended outside the Prairieland ICE detention center in Alvarado, Texas, where an officer was shot. (Prosecutors do not allege that Sanchez Estrada or Rueda were involved in the shooting.) The home-spun zines at issue contain no plans for any shooting, and under normal circumstances, they would clearly be deemed constitutionally protected speech under the First Amendment. But the government’s concealment theory only makes sense if it views merely having the literature as criminal.

Once possessing literature is considered criminal, it opens the door to corollary charges, like transporting literature to conceal evidence or the “offense” of possessing it. That’s what happened to Sanchez Estrada. What other crime could the magazines have incriminated Rueda of?

Last month, activist Lucy Fowlkes became the 19th person indicted in connection with the same Texas protest. Fowlkes’s alleged crime is using Signal, the encrypted messaging app made famous by Pete Hegseth, telling people how to delete messages, and removing people from group chats, which government lawyers argue amounts to “hinder[ing] prosecution of terrorism,” a first-degree felony.

Historically, the U.S. government has always used disenfranchised populations as a test case to develop both strategy and legal precedent for infringing on constitutional rights before exporting them to society as a whole. Before incarcerated people faced retaliation for possessing books, African slaves were frequently punished for reading the Old Testament out of fear that the Exodus story might inspire them to dream of freedom. In some places, proponents of slavery reconciled their desire to convert slaves to Christianity with their fear or rebellion by creating a heavily redacted “Slave Bible.”

Land confiscated from Native populations eventually became eminent domain. Former FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s surveillance of Black leaders during the civil rights movement gave justification for George W. Bush’s invasive Patriot Act and mass surveillance of civilians. Now, the Trump administration is taking a page directly out of oppressive prison authorities’ playbook.

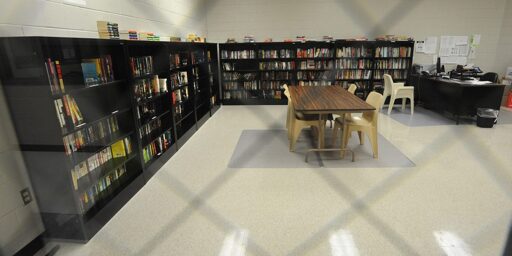

American prisons have never been much for the First Amendment, and now, the Trump administration is exporting prison-style censorship to the general population. In tactics that are easily recognizable to incarcerated people like me, they’re doing it in the name of “security.”